Aristotle and the 'Virtue paradox': The Battle of Virtue vs. Virtue Signalling

How Ancient Ethics Got A Makeover in the Age of Likes, Shares, and Moral Performances.

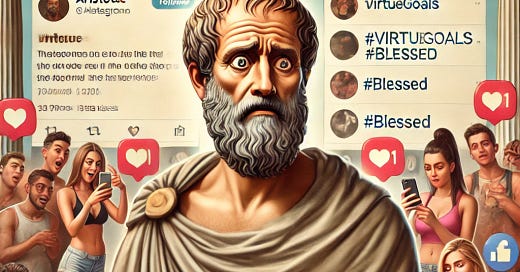

In today’s world, where the superficial often triumphs over the substantial, Aristotle’s wisdom on virtue feels as out of place as a philosopher at a reality TV convention. Imagine Aristotle, bearded and bemused, watching from the afterlife as humanity replaces his carefully considered ethics with the facile performance of moral superiority. In a world where virtue signalling reigns supreme, one might wonder: have we become more virtuous or simply mastered the art of looking good?

The Virtue Paradox Defined

The "Virtue Paradox" is the modern phenomenon where the more we publicly perform acts of virtue, the less likely we are to cultivate genuine virtue. It’s the strange, almost counterintuitive reality that, in an age where we have more ways than ever to showcase our good deeds, a true moral character might be in decline. In a world obsessed with appearances, the Virtue Paradox isn’t just a philosophical curiosity—it’s a reflection of how our ethical compass might be pointing us in the wrong direction. And, let’s be honest, the idea that you could become a moral black hole while collecting likes on your latest "charitable" Instagram post is both hilarious and horrifying.

Why Academic Philosophers Missed It

As for why academic philosophers might have missed this paradox, and to my understanding, they have, it’s simple: they’ve been too busy arguing about whether Aristotle’s concept of eudaimonia can be reconciled with modern theories of happiness or whether his ethics can be applied in today’s fragmented moral landscape. Or why Professor X’s interpretation of claim a is insufficient because Professor Y has clearly shown that claim a is intuitive, and Professor Y was not dealt with by Professor X. Meanwhile, the rest of the world moved on, trading in their moral integrity for social media clout. Perhaps if Plato’s Forms had an Instagram account, more attention would have been paid to this issue.

I believe there’s something ironic in the image of philosophers sitting in their ‘ivory towers’, meticulously dissecting ancient texts while the world outside burns with the fever of performative virtue. It’s almost as if, in their pursuit of abstract ethical truths, they’ve forgotten that those truths are supposed to apply to the real world. In this sense, the academic focus on the minutiae of philosophical theory has become a kind of intellectual virtue signalling—a way to demonstrate intellectual superiority without necessarily engaging with the practical, messy reality of human life.

One might even argue that this detachment is precisely why the Virtue Paradox has gone unnoticed by the philosophical elite. When your primary concern is whether Aristotle’s ethics can be reconciled with contemporary moral theory, it’s easy to overlook the fact that most people don’t live their lives according to carefully crafted philosophical doctrines. Instead, they navigate a world where appearances often matter more than substance—a world where the most "virtuous" acts are the ones that get the most likes, shares, and retweets.

In ignoring the real-world implications of virtue signalling, academic philosophers have become complicit in the phenomenon they’ve overlooked. By focusing on theoretical debates, they’ve allowed the practical application of virtue to be co-opted by those more interested in appearance than substance. And in doing so, they’ve ceded the moral high ground to the very people who are most adept at playing the virtue-signalling game. It is high time that Academic philosophers attend to this characterisation and engage with the world once again.

Aristotle’s Blueprint for Virtue: A Model for Moral Development

Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics isn’t just a dusty tome gathering philosophical cobwebs; it’s a roadmap for how to become a genuinely good person. Aristotle argues that virtue is cultivated through habituation—a practice perfected by consistently performing virtuous actions under the guidance of genuinely virtuous role models. These role models, paragons of moral excellence, serve as lodestars in the moral development of others. In other words, if you want to learn how to be courageous, you don’t just read about it in a self-help book; you watch someone like Achilles face the chaos of battle without flinching—though let’s be honest if Achilles were around today, he’d probably be more concerned with the number of followers he gained by live-streaming his heroic exploits.

But Aristotle’s vision goes deeper. He doesn’t just want you to copy these role models like some moral monkey—he wants you to understand the why behind their actions. Virtue, for Aristotle, isn’t merely about doing the right thing; it’s about being the right kind of person. This means developing deep-seated character traits through repeated, deliberate actions aimed at the good, which requires more than surface-level mimicry. It’s about internalising the principles that guide virtuous behaviour so that you’re not just going through the motions but genuinely embodying the virtues in everything you do.

Today, our role models have shifted from the virtuous to the visibly virtuous. Aristotle’s paragons of moral excellence have been replaced by social media influencers, who, let’s face it, are more concerned with looking good than being good. If you think I’m exaggerating, consider the difference between learning courage from a war hero who’s faced real danger versus an Instagram influencer who’s built a brand around “bravery” by posting pictures from the edge of a cliff (carefully calculated to get the best angle, of course). The former teaches you about the virtue of courage in the face of adversity; the latter teaches you that courage is all about finding the perfect filter.

In Aristotle’s world, virtue wasn’t a performance but a way of life. He would likely be horrified by today’s culture, where the appearance of virtue often takes precedence over the substance. To Aristotle, the idea that you could "perform" virtue for the sake of public approval would be antithetical to the very concept of virtue itself. He believes virtue is cultivated internally through rigorous self-discipline and an unwavering commitment to moral principles. It’s not something you switch on when the cameras are rolling and then forget about when the spotlight moves on.

But let’s not give Aristotle too much credit without acknowledging the complexities. It’s easy to idealize the past and imagine that everyone in ancient Greece was walking around with a perfectly calibrated moral compass, following the guidance of virtuous role models. In reality, even Aristotle knew that not everyone had access to these paragons of virtue—hence his emphasis on the importance of good laws and societal structures to guide behaviour when role models are lacking.

In today’s world, where media and public perception often shape those societal structures, distinguishing between genuine virtue and its more superficial, Instagrammable cousin is challenging. Aristotle’s model of moral development demands more from us than just imitation; it demands understanding, reflection, and, most importantly, intention. It’s about cultivating virtues that are deeply rooted in our character, not just stapled on like a cheap accessory.

Virtue Signalling: The New Moral Order

Today, Aristotle’s virtuous role model has been replaced by the "Virtue Influencer." These modern-day moral guides aren’t admired for their intrinsic goodness but for their ability to curate the appearance of virtue. Consider the countless social media personalities who build their entire brands around charitable acts and activism, often ensuring every moment of their "selflessness" is captured and shared for maximum engagement. The question isn’t whether their actions are beneficial—they often are—but whether they’re motivated by genuine concern or the desire to boost their online following. Are these influencers modern Aristotles, leading by example, or are they merely the faces of a new kind of virtue that exists only in the filtered frames of an Instagram post?

If we’re being honest, the answer is as airbrushed as the images on their feeds. These influencers aren’t just failing to live up to Aristotle’s standards—they’re actively rewriting the rules of virtue to suit a digital age where appearance is everything and substance is an afterthought. Instead of embodying the virtues Aristotle extolled—courage, temperance, justice, wisdom—they’ve crafted a new set of "virtues" that thrive only in the spotlight, vanishing as soon as the cameras are off. Their "goodness" isn’t about living a life of ethical integrity but about maintaining a brand, where the currency isn’t moral excellence but the approval of the faceless masses who double-tap their screens.

Aristotle’s vision of virtue as a deeply ingrained character trait cultivated through consistent and intentional action is reduced to a performance—a carefully staged act designed to garner likes, shares, and follows. It’s as if we’ve traded the quiet dignity of true virtue for the garish spectacle of public validation. The result? A world where the worth of your soul is measured not by the content of your character but by the number of "hearts" your latest post receives. Aristotle must be spinning in his well-ordered, golden mean grave.

And let’s not pretend this is some harmless trend. The real tragedy here is that these influencers, with their perfectly curated "virtuous" personas, aren’t just fooling their followers—they’re fooling themselves. When the applause is constant and the praise unearned, it’s easy to believe you’re as virtuous as your feed makes you out to be. But like any illusion, this one shatters the moment reality creeps in. When the likes dry up, so does the "virtue," leaving behind nothing but the hollow echo of a performance that was never real to begin with.

These influencers have managed to turn virtue into a commodity—a shiny, disposable product that’s only as valuable as its marketability. In this new moral economy, authenticity is the first casualty. What matters is not what you do when no one’s watching but what you can make people believe you’ve done when everyone is. It’s a moral shell game where the only winners are those who’ve perfected the art of appearing virtuous without the burden of actually being virtuous.

So, no, these influencers are not the modern Aristotles we might hope for. They are the carnival barkers of a new moral order, selling us the illusion of virtue while pocketing the profits of our collective gullibility. And we, eager to buy what they’re selling, play along, content with the shallow satisfaction that comes from believing—if only for a moment—that we’re better people simply for having followed them.

This phenomenon isn’t limited to individuals. Corporate virtue signalling is rampant—companies slap labels like "green," "ethical," and "inclusive" on their products, all while engaging in practices that directly contradict these labels. It’s as if Aristotle’s ergon—the idea that the good for humans lies in fulfilling their characteristic function through genuine virtuous activity—has been replaced by a boardroom strategy session on how to look good without actually doing good.

The Case for Visible Virtue: Can Public Displays Still Inspire?

There is, of course, a counter-argument that suggests visible acts of virtue, even when somewhat superficial, serve a valuable social function. Aristotle himself recognized that societal norms and laws play a crucial role in shaping virtuous behaviour, suggesting that public displays of virtue might encourage others to follow suit. The logic is sound: if people see others, especially those they admire, engaging in virtuous acts, they might be more inclined to do the same. After all, in a world teetering on the edge of moral apathy, even a little visible virtue could go a long way, right?

Take, for instance, the phenomenon of celebrities using their platforms to promote various causes. We’ve all seen it—your favourite actor or pop star takes to social media to advocate for saving the whales, planting trees, or supporting the latest social justice movement. The idea is that their influence will ripple out, inspiring fans to follow suit. And sometimes it works—donations spike, awareness spreads, hashtags trend. It’s visible virtue in action, nudging the masses toward better choices through the power of example.

Yet, while these visible acts can lead to positive outcomes, the real question is whether they contribute to genuine moral development. Are we all just playing a game of ethical dress-up, where the person who can shout "I care!" the loudest wins, regardless of whether they actually give a damn?

In his analysis of Aristotle’s ergon inference, Gomez-Lobo reminds us that true virtue isn’t about surface-level actions but about fulfilling one’s characteristic function with sincerity and depth. Aristotle’s notion of ergon—the idea that the good for humans lies in the proper functioning of our unique rational capacities—emphasizes the importance of intention and understanding behind virtuous acts. When public virtue becomes more about optics than substance, we risk cultivating a society that’s all image and no substance—a moral shell game where everyone’s a winner, yet we all lose.

Consider the recent trend of social media influencers and celebrities posting pictures of themselves at protests, holding signs they probably didn’t make, surrounded by a crowd they may or may not even know. These posts get thousands of likes and shares, sparking comments like "So brave!" and "What a role model!" But then the curtain pulls back, and we see the same influencers jetting off on private planes to vacation in some tropical paradise, leaving their "commitment" to the cause on the tarmac. The real question isn’t whether they’re raising awareness (they are) but whether they’re actually committed to the virtues they’re publicly displaying—or if it’s all just part of their brand strategy.

And this isn’t just a hypothetical. During the height of the Black Lives Matter protests, many influencers were caught staging their involvement—literally stopping by protests just long enough to snap a few pictures for Instagram before heading back to their air-conditioned apartments. The "support" was more about capturing the perfect shot than standing in solidarity, leading to a backlash that exposed the hollowness of such performative acts. It’s the modern-day equivalent of wearing a toga at a philosophy convention: sure, you look the part, but does anyone really believe you’ve read Plato?

The risk, as Gomez-Lobo suggests, is that such superficial displays can erode the very concept of virtue itself. When society becomes accustomed to valuing virtue based on its visibility rather than its authenticity, we may begin to lose sight of what it means to be truly virtuous. The result is a culture where ethical behaviour is performed not out of a sincere commitment to doing good but out of a desire to be seen as good. It’s as if we’re all starring in our own personal morality play, but the audience doesn’t realize the curtain never comes down, and the actors never leave the stage.

Moreover, the reliance on visible virtue can lead to what some call "moral licensing." This is the phenomenon where individuals or organizations feel entitled to act less ethically in other areas after performing a visible act of virtue. For example, studies by Merritt, Effron, and Monin have shown that people who engage in acts perceived as morally good are more likely to subsequently make choices that are ethically questionable. This effect has been observed in various contexts, such as people who endorse a socially responsible product later feeling justified in making selfish or indulgent choices.

While potentially inspiring, Merritt, Effron, and Monin's research illustrates how public acts of virtue can paradoxically decrease overall moral behaviour by giving individuals a psychological "license" to behave less ethically afterwards. It’s like buying a salad at lunch and thinking it cancels out the chocolate cake you ate for breakfast—it might make you feel better, but it doesn’t change the calories.

Nevertheless, while public displays of virtue can undoubtedly inspire and guide behaviour, they must be carefully scrutinized for their true impact on moral development. Aristotle would likely caution that without the right intentions and understanding behind these acts, they risk becoming hollow performances rather than genuine expressions of virtue. The challenge, then, is to ensure that visible virtue serves as a gateway to deeper moral engagement rather than a substitute for it.

The Dark Side of Virtue Signalling: A Modern Tragedy

The real tragedy of the Virtue Paradox is that it doesn’t just dilute genuine virtue—it actively undermines it. While Aristotle emphasised that virtue must be pursued for its own sake and as an end in itself, modern virtue signalling treats virtue as a means to an end—whether that end is social approval, political advantage, or financial gain. This isn't just bad philosophy; it’s bad living.

Consider the case of certain celebrities or influencers who publicly donate large sums to charity but ensure that their contributions are widely publicised. It is not difficult to suppose a high-profile celebrity pledging a sizable donation to a disaster relief fund, only for it to be later revealed that the donation was either significantly delayed, incomplete, or contingent on favourable media coverage. The criticism here isn’t that the donation itself isn’t beneficial—after all, the funds contribute to relief efforts—but that the act was more about securing a positive public image than genuine concern for those in need.

This kind of behaviour exemplifies Aristotle’s concern that virtue, when pursued for the sake of something else—whether it be fame, public approval, or financial gain—ceases to be true virtue. The donation, though impactful, is tarnished by the ulterior motive, turning what could have been an act of genuine altruism into a carefully calculated PR move. Aristotle would argue that such actions lack the true intentionality required for moral development; they are performed not out of a desire to do good but out of a desire to be seen doing good.

Moreover, the superficiality of such actions can create a feedback loop where individuals and institutions feel pressured to continually outdo one another in their public displays of virtue. This "virtue competition" diminishes the sincerity of actions and shifts the focus from meaningful change to maintaining a virtuous image. The result is a society more concerned with the optics of virtue than the substance, where moral growth is stunted by the practices meant to promote it.

In this context, Aristotle’s insistence on the importance of intentionality becomes crucial. The philosopher understood that virtue is not merely a matter of doing the right thing; it is about doing the right thing for the right reasons. Virtue signalling, by its very nature, often lacks this depth of intention. When the primary goal of a supposedly virtuous act is to be seen by others, the act itself loses its moral value. Instead of fostering genuine virtue, such actions can lead to a kind of ethical complacency, where the appearance of virtue suffices, and the harder work of true moral development is neglected.

Counter-Argument: Could ‘Virtue Signalling’ Be a Stepping Stone?

Some might argue that even if virtue signalling is superficial, it could still serve as a stepping stone toward genuine virtue. By engaging in public displays of virtue, individuals might begin to internalise these values over time. This notion aligns with Aristotle’s belief that moral development often starts with external actions before these actions are fully integrated into one’s character.

Indeed, Aristotle would acknowledge that habits form character. If someone repeatedly performs virtuous acts, even if initially for the wrong reasons, there’s a possibility that these actions could become genuine over time. This idea is akin to the "fake it till you make it" approach—by acting as though one possesses certain virtues, one might eventually cultivate them for real. Aristotle might argue that the practice of virtue, even when motivated by less-than-pure intentions, could still lead to the internalisation of those virtues. Over time, what begins as a desire for public approval could evolve into a genuine commitment to ethical principles.

However, while there is a kernel of truth in this, it’s important to recognize the limitations. Burnyeat’s interpretation of Aristotle, supported by other scholars like Kenny, would caution that for Aristotle, the critical component of moral development is the intentionality behind actions. Aristotle believed that virtues are formed through deliberate practice, with the understanding that the goal is not just to perform good acts but to become a good person—someone who acts virtuously out of a deeply ingrained sense of moral purpose.

When actions are performed primarily for public approval, they are unlikely to lead to genuine moral growth. Instead, they reinforce a cycle of superficiality, where the appearance of virtue is continually mistaken for the real thing. This is particularly problematic in a society where public recognition often becomes the primary motivator for moral behaviour rather than an internalized commitment to doing good for its own sake.

Consider the social phenomenon of "performative activism." While raising awareness about social issues is undoubtedly important, the practice of posting hashtags, attending rallies, or making statements primarily for the sake of being seen as "on the right side" can lead to a hollow form of activism. The danger lies in mistaking these outward signs of support for true engagement with the issues at hand. As Aristotle would argue, these actions do little to cultivate real virtue without a genuine commitment to the underlying moral principles.

Thus, while public displays of virtue might have some role in encouraging certain behaviours, they fall short of fostering the kind of deep, reflective moral development that Aristotle envisioned. The real danger of virtue signalling lies in its potential to deceive both the individual and the society into believing that moral growth has been achieved when, in fact, it has not. This deception is the true tragedy of the Virtue Paradox: a world where the more we signal our virtue, the further we may drift from actually embodying it.

Conclusion: The Virtue Paradox Realized—And Our Role in It

So here we stand, in the midst of a virtue paradox that would make Aristotle’s head spin faster than a politician during an election cycle. We’ve traded the slow, deliberate cultivation of moral character for the instant gratification of public approval, reducing virtue to a commodity that’s only as valuable as its marketability. The modern world has taken Aristotle’s well-worn blueprint for virtue and used it to paper over the cracks in our collective conscience.

In this new moral order, where the appearance of goodness matters more than the substance, we’re all players in a grotesque theatre of ethics. And let’s be honest—none of us are entirely innocent. Even as I sit here, typing away for this Substack piece, I’m not immune to the very forces I’ve been criticising. After all, what am I doing if not participating in the same performance? I’m crafting arguments, honing my wit, and, yes, seeking the approval of you readers. We writers are in the business of persuasion, of shaping opinions—and if we’re really being honest, of getting those sweet, sweet likes and shares.

But before you accuse me and others of moral hypocrisy, let’s get one thing straight: we’re acutely aware of the irony [I hope]. We know we’re part of the very system we’re critiquing. The difference, we’d argue, is that we’re not pretending our words are the final bastion of virtue in a world gone mad. We’re not here to claim the moral high ground but to point out the ridiculousness of the climb. We’re the jesters in this absurd court of ethics, poking fun at the so-called virtue kings who strut about in their invisible robes of righteousness (I am relying on a lot of assumptions there, but in my own case, it is faultless(!)).

And maybe that’s the point. Perhaps the best defence against the hollow spectacle of modern virtue is a good laugh at its expense. After all, Aristotle didn’t write his Nicomachean Ethics to impress anyone—he based it on lectures to help people live better lives. If my contribution to this discussion does anything, let it be this: to remind us all that true virtue isn’t about how we’re seen but about who we are when no one’s looking.

So, as we log off, close our laptops, and return to our daily lives, let’s take a moment to consider whether we’re truly living following the virtues we so often flaunt online. Are we cultivating real courage, temperance, and wisdom, or just playing a role for the digital audience? In a world where virtue signalling has become the norm, the real act of rebellion might just be practising genuine virtue—quietly, consistently, and without the need for applause.

Because in the end, when the screens go dark, and the followers fade away, it’s not the number of likes that will define us. It’s the substance of our character, the strength of our convictions, and the quiet, uncelebrated actions we take in pursuit of the good. Aristotle knew this, and deep down, so do we.

Reference list

Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by W.D. Ross.

Burnyeat, M.F. Aristotle on Learning to Be Good. In Essays on Aristotle’s Ethics, edited by A.O. Rorty, University of California Press, 1980

Gomez-Lobo, Alfonso. "The Ergon Inference." Phronesis, vol. 34, no. 2, 1989, pp. 170-84.

Kenny, Anthony. Aristotle’s Ethics. Oxford University Press, 1992

Merritt, A. C., Effron, D. A., & Monin, B. (2010). "Moral Self-Licensing: When Being Good Frees Us to Be Bad." Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(5), 344-357.

In the Sermon of the Mount, Christ warned us against people who publicly displays their virtues.

Appreciate this article very much. I think you nailed the tragedy part. Particularly when you mentioned how the virtue signalers being to believe in their own virtue. There is virtually nothing more dangerous to moral development than self-deception.